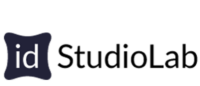

Taboos and stigmas are like ‘’open public secrets’’ and often dealing with these topics can be challenging due to the negative societal view. However, taboos and stigmas can have a strong impact on the well-being of people, therefore, addressing these subjects is of high importance (Field, Sinclair & Valdes, 2010). One taboo that exists around the world is the one of menstruation (Thakur et al., 2014), but in the low middle-income countries the effect of the taboo can have an even stronger negative impact on the lives of women. In India, the strong societal negative view of menstruation being dirty and unclean (Omidvar & Begum, 2011), influences their education, health, religion, relationships and overall well-being (figure 1). It stops women from achieving their full potential (FSG, 2016). In the patriarchal country of India, women conduct their periods in secrecy and shame, without involving men, though often being the breadwinners in the family, men directly impact lives of women and consequently, their periods. Efforts are trying to deal with the correlating problems through provision of menstrual education or education on menstrual hygiene management, however, none of them address the underlying problems of stigma and shame that prevents from dealing with the subject openly (Lieberman, 2018). The aim of the project was to enable discussion as the first step towards taking menstruation out of the light of stigma and taboo to enhance the well-being of women.

Menarche introduces girls to the cultural baggage of secrecy and shame, where they must hide and control the messiness that surrounds the evidence of their womanhood (Allen et al., 2011).

Figure 1. Different aspects in the life of a woman in India which menstruation can affect (work, religion, financial issues, relationship with men, health, family, education, society, personal issues); (Own ill., 2018.)

Family focus

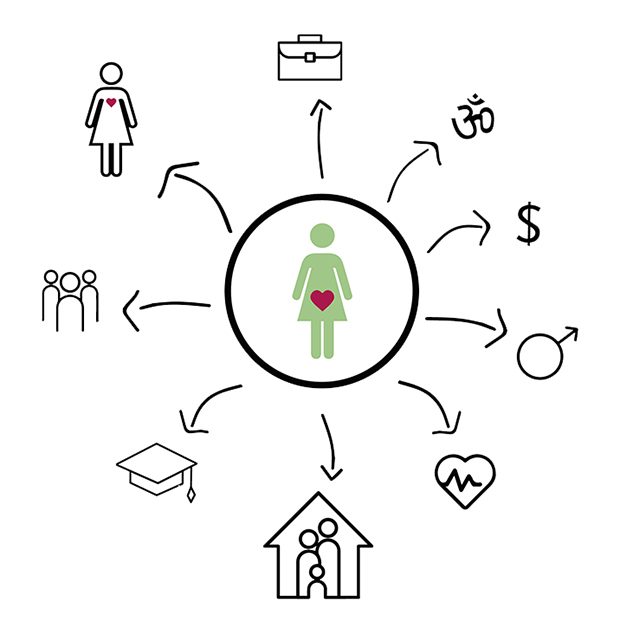

Indian society and culture are largely collectivistic and family values are put on the forefront (Jacobson, 2014). Therefore, to address the taboo and create an intervention, the comfort and security of the family home was taken as the context of action. Focus of the project was made on the younger generations as they are easier to influence since they are still in the age of forming. The tests showed how a lot of girls are shy and can feel anxious when it comes to menstruation due to the silence pervading this topic. Through research, the need of focus was shown to be the pre-menstruating girls (figure 2). It was found how pre-menstruating girls are not aware of menstruation nor properly informed on conducting their periods which has shown to create emotions of anxiety for the upcoming menarche. Including all members of the family home was essential, especially the fathers who are heads of the house and thus have a direct impact on the lives of women and the way they conduct their periods. Moreover, it was found how a positive view of fathers and male members on menstruation creates higher confidence of girls and a positive attitude towards menstruation.

Figure 2. The defined triggers, abilities and motivators to switch from the current behaviour towards the desired behaviour

‘‘If they(girls) are not free in the home they won’t be free out. Freedom and lack of freedom happens at home. And menstruation and puberty changes that happen with them are the first opportunity to set them free.’’ (Father test 9)

Gamification and humor to tackle the taboo

Taboos are sensitive subjects and require a careful approach to avoid opposition. It was important to find a subtle way to bring the discussion on menstruation among all family members, which led to gamification. The engaging and interactive aspect of the game can distract from the existing taboo and stigma allow discussion to occur naturally as an aspect of game playing. Moreover, the usually uncomfortable and awkward discussion can be turned into a fun competition. Gamification can as well be used for changing the behaviour by tailoring new behaviour with a repetitive exposure of certain information (taken from interviews). This finally contributes to the normalization of the subject.

Humour, on the other hand, can be used as an ice-breaker to talk about something that is initially uncomfortable. Furthermore, it can be used as a way to reframe the stigma (Van der Lande & Vegter, 2015). Humor can also help in normalizing those subjects. Dr Ivan Brown from the University of Toronto, who works on special education and disabilities, states the benefits of using humour when combating stigma: ‘‘Humour gives us the opportunity to explore things beyond our usual mindset. Most problems will disappear or become less problematic, when there is something to laugh about (…)’’ (Van der Lande & Vegter, 2015).

Process

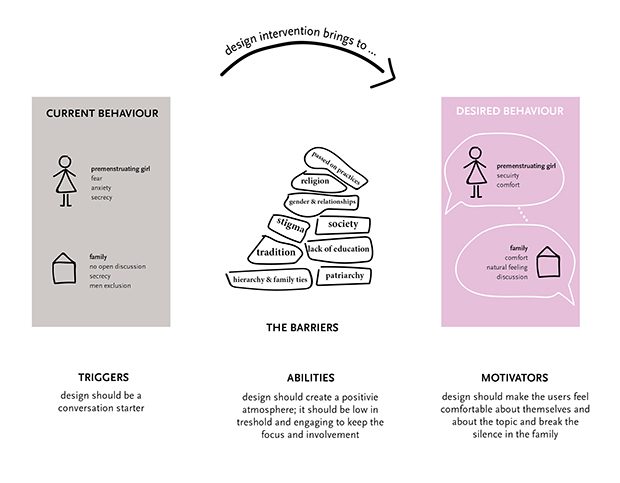

The project included a 3-month field research in India (figure 3). The first part of the research in India included interviews with experts from different fields whose work in some way involves menstruation. This contributed to a deeper understanding of the context and the existing practices.

Figure 3. The process of the project – desk research was conducted in Netherlands, which was followed by field research in India, and concluded with the form giving part in Netherlands

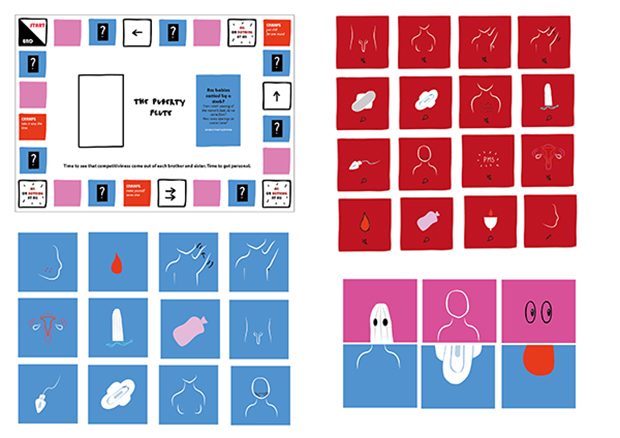

The second part of the research was testing with families. The test samples were nuclear urban families with at least one daughter of the age of 11-18 years old. The tests were conducted with interviews and tests of the 4 games (figure 4) with the research through design approach, to get a response to the design, but also honest reactions to the stigma and taboo.

Figure 4. 4 designs (described top to bottom) – board game ‘‘Puberty Flute’’, a combination of pictionary, charades and alias ‘‘Giggles’’, ‘‘Memory game’’, pairing game ‘‘Mix-A-Body-Match’’ (Own design, 2019.)

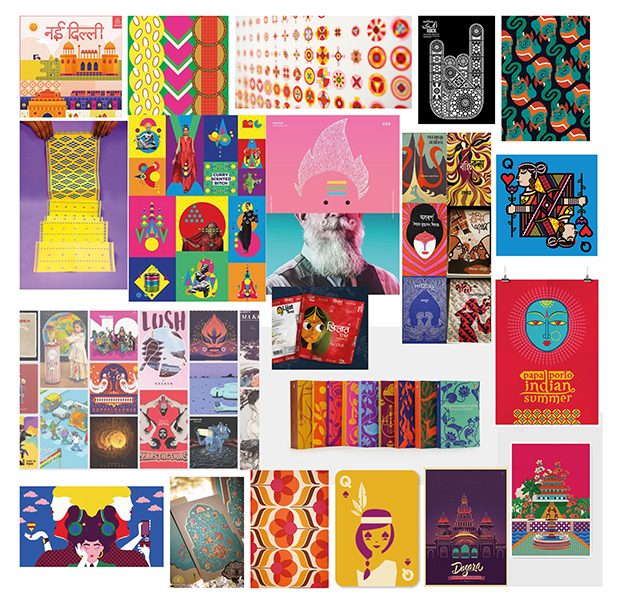

All the games were customized to the culture of India as it has shown to increase the trust in the user (Sorcar et al., 2017) and to seem natural to the family, and not like an imported material. The explorations were made through the patterns, the colour combinations and the visual characters/content of the cards (figure 5).

Figure 5. Exploration of the forms, colours and designs in India

Results

The tests have proved that all families, no matter the strata or their educational level, experience initial discomfort when exposed to the topic of menstruation due to the tradition and the negative societal view. Despite the taboo, the families were reluctant to stop game playing. Certain aspects of the game – competitiveness or timing and humour made the family involved in the game and enjoy it, even though it was on menstruation.

The games proved to serve as a natural tool for creating conversation. Conversations on menstruation usually do not occur in the family. They are uncomfortable, but with the help of the games it ‘‘was a less awkward way of speaking the same thing, but not going through the cons of having the conversation.’’

Mix-A-Body-Match

Figure 6. The final concept, Mix-A-Body-Match consist of a colourful box, with the educational booklet and the cards

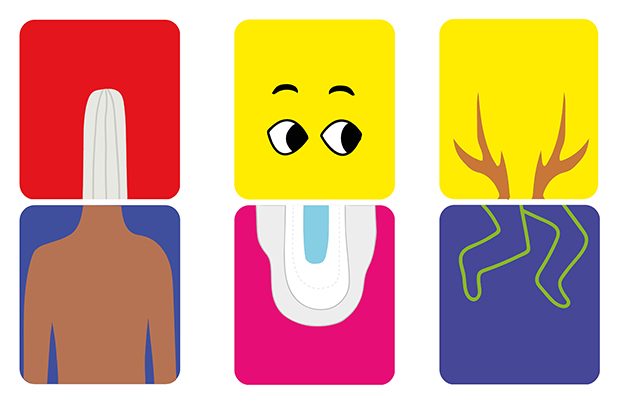

The concept of the pairing game, Mix-A-Body-Match (figure 3), was taken as a final one, as it has created the best atmosphere in every family. The aim of the game is to win the game by creating the most funny pair out of the given material. Mix-A-Body-Match was different from other 3 designed games as it included other con-tent than puberty and menstruation, thus making the game playing entertaining, and even surprising and less serious. Players could get creative and imaginative with the content that was seen as a taboo and pair them with daily objects to turn the taboo into a humorous content. By using other content apart from puberty, the game has put menstruation on the same level of discussion as other mundane objects, such as flip-flops, funny eyes etc. (figure 4) and that way presenting menstruation as something that is not avoided or hidden.

Figure 7. Funny combinations made during the testing with Mix-A-Body-Match

The humorous aspects of the game and the laughter eased the topic and allowed for an easier conversation. Mix-A-Body-Match was also shown as the best fitting concept for the youngest generations as it did not require prior knowledge and removed discomfort of involvement in such a topic. Moreover, the concept was favoured by most male members as it presented the topic of menstruation as simple, easy and light, and not the usually uncomfortable one.

This work has been presented at Senses&Sensibilitiy 2019, Lisbon, Portugal

References

Fields, B., Sinclair, R., Valdes, A. (2010). Ideo: How to Turn Social Taboos Into Innovative Products, retrieved from: https://www.fastcompany.com/1662478/ideo-how-to-turn-social-taboos-into-innovative-products

FSG (2016.) Menstrual Health in India | Country Landscape Analysis, retrieved from http://menstrualhygieneday. org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/FSG-Menstrual-Health-Landscape_India.pdf

Jacobson, D.(2004.) Indian Society and Ways of Living, retrieved from: https://asiasociety.org/education/indian-society-and-ways-living

Lieberman, A. (2018.) Menstrual health, while excluded from SDGs, gains spotlight at UN political forum, retrieved from: https://www.devex.com/news/menstrual-health-while-excluded-from-sdgs-gains-spotlight-at-un-political-forum-93137

Omidvar, S., Begum, K. (2011). Factors influencing hygienic practices during menses among girls from south India-A cross sectional study. International Journal of Collaborative Research on Internal Medicine & Public Health. 2. 411-423.

Sorcar, P., Strauber, B., Loyalka, P., Kumar, N., Goldman, S. (2017.) Sidestepping the Elephant in the Classroom: Using Culturally Localized Technology To Teach Around Taboos. ACM CHI 2017.

Thakur, H., Aronsson, A., Bansode, S., Stalsby Lundborg, C., Dalvie, S., & Faxelid, E. (2014.) Knowledge, Practices, and Restrictions Related to Menstruation among Young Women from Low Socioeconomic Community in Mumbai, India. Frontiers in public health, 2, 72. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2014.00072

Van der Lande, I., Vegter, L. (2015.) Humour is necessary to overcome stigma, retrieved from: https://disabilitystudies.nl/sites/disabilitystudies.nl/files/interview_ivan_brown_fin_ervaringswijzer.pdf